curatorial text

Fernando Davis

The bad handwriting. Alberto Greco's papers

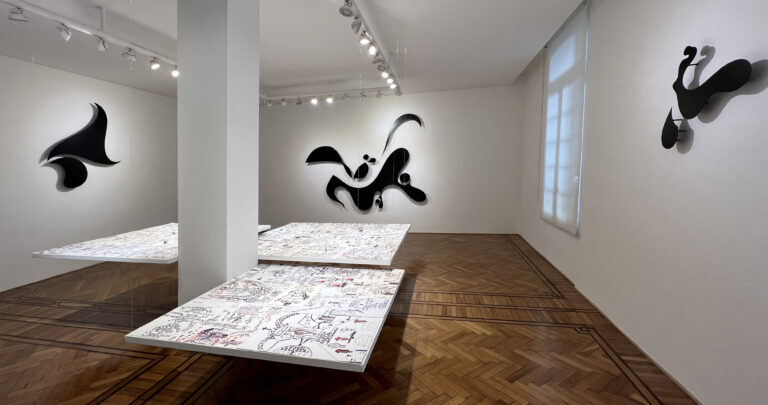

In the drawings he made in Madrid and Piedralaves between 1963 and 1964, Alberto Greco combined heterogeneous fragments and remnants of images and texts that press and involve antagonistic temporalities. In Antonio Saura’s words, Greco conceived his works as “a journal of additions and overlays, as if obeying an inner seismograph”. The ink stroke proliferates in these drawings of tight and knotted graphics, merging at times into illegible and rabid handwriting, to finally become an indecipherable text. It becomes handwritten, stain, trace, strikethrough, scribble. The “bad handwriting” betrays the correct calligraphy that is molded through a whole disciplinary pedagogy of both body and hand. A bad writing whose flow – inconstant, twisted – obeys the intensities of the body and the experience of drift within the city.

The characters in Greco’s works cross the teratological and the pornographic. The body, open, shown both as penetrable and penetrating, in images that refer to obscene graffiti walls of public toilets, homosexual places that Greco frequented and signed, as he states in the synthetic chronology of his actions of living art included in his Great manifesto-roll art Vivo-Dito. Greco “stains” the drawing with the indecorous traffic of the signs of promiscuous sexuality sanctioned as shameful, which is negotiated in the semi-clandestinity of a bathroom. “Dandy lumpen”, as Diego Trerotola called him, and flâneur puto, Greco makes use as a strategy that crosses its work the act of wandering through the city and the drifting of the body that decentralizes the disciplinary orders of the urban layout in the “lost” time of the strolling, Collage and montage interrupt the continuity of the drawing with marks of a drift in the city, thus spacing text and image. Greco introduces multiple references to urban advertising and the graphic press, popular culture and mass media such as comics, romantic novels or cinema: tango lyrics or pasodoble, references to the Marx brothers or cartoon characters, along with fragments of conversations or stories of his wanderings in the city and typographies that refer to the advertising signs on walls and shop windows.

Writing diagrams a nomadic device that traffics and decentralizes registers and intensities of the word that goes from fictional narration to an autobiographical narrative, from poetry to conversation, from letter to the manifesto. His texts tend to excess and excess, to melodrama and camp, to the eschatological anecdote, and out-of-place stories. Greco dispersed the writing in his drawings, where he included annotations and ideas-in-process that in some cases can be read in dialogue with his literary texts. He used rolls, notebooks, pads to take note of all these. In Madrid, in 1963, he wrote his “police account” Guillotine died guillotined in a pad, intertwining fiction with biographical references. The characters in the text are the people with whom he lived or frequented daily. Guillotine takes as his starting point the assassination of US President JF Kennedy in November 1963 – an episode around which Greco produced a series of paintings and collages – as well as the reference to the murder of his assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald while being transferred to prison. In the notes of Greco’s police account, the character of Alberto wants to kill Torrente, but in turn, it is Torrente who murders him with a shot in a scene that is televised, superimposed on the news of the murder of Oswald. Guillotine can be approached from the assembly procedure with which Greco composed his drawings. The collage introduces cuts and discontinuities in the writing, the plot is delayed between anecdotes of Greco’s adventures in Madrid, absurd dialogues and references to the process itself of writing the text in which he is working on. Towards the end, in a conversation with Brigitte, Alberto complains about the difficulty in concluding his story:

– Guillotin, it’s me … – At last, Gonzalo has insisted so much that you finish the story, that you will end up dying. – But … isn’t he the one who is going to die? – Sure. – But how can you kill him? I’m fed up! The day I got to this house, do you remember Brigitte? […] I told Gonzalo that I wanted to write a police story and that he would do the illustration before reading it… then I went up to my room. I can stand this any more! I am fed up of writing! And I started writing without knowing what to write not what I felt at that time … I was trying to add police elements … the truth is that I never read a story by Gonzalo or anyone else nor a crime or suspense novel. I know the best is Simenon but I never read it … I looked at it at Doña Maura’s house and nothing else… It was well done but I didn’t follow it, I find it impossible to concentrate …

During the Spanish summer of 1963, Greco spent a season in Piedralaves, a town located in the province of Ávila. “Villa Grequissimo” or “el Grequissimo Piedralaves”, as he used to call the place, was the setting in which he carried out a series of Vivo-dito that was documented by photographer Montserrat Santamaría. Greco had started his live art actions in 1962, on the streets of Paris, pointing and signing people, objects, and situations with a circle of chalk. While passing through the city of Genoa, in July of that same year, he coined the concept of Vivo-dito and covered several walls with a poster, printed in Italian, with his “Manifesto Dito dell’Arte Vivo”: “Living art is the adventure of the real. The artist will teach how to see not with the painting but with the finger. Artists will teach us to see again what happens on the street […] We should get into direct contact with the living elements of our reality: movement, time, people, conversations, smells, rumors, places, situations ”. Greco multiplied the insubordinate gesture of the Vivo-dito in every city he visited: Rome, Madrid, Buenos Aires, New York. In Piedralaves he also made his Great manifesto- art roll of Vivo-Dito, an extensive roll of paper about 300 meters long by 10 centimeters wide, which he displayed on the streets in different signs, sometimes with the collaboration of the people of the place. As in the drawings he made back then, the Great manifesto-roll, which Greco was intervening and writing with the course of his actions in Piedralaves, combines the collage of photographs and advertising images, ink drawings, tango lyrics, autobiographical stories, annotations about Vivo-Dito and excerpts from letters and conversations. One of his texts announces: “Greco clarifies and explains his performance in Christ 63 / Tómbolas / Tangos / Crime / Comics / Recipes / Family correspondence”.

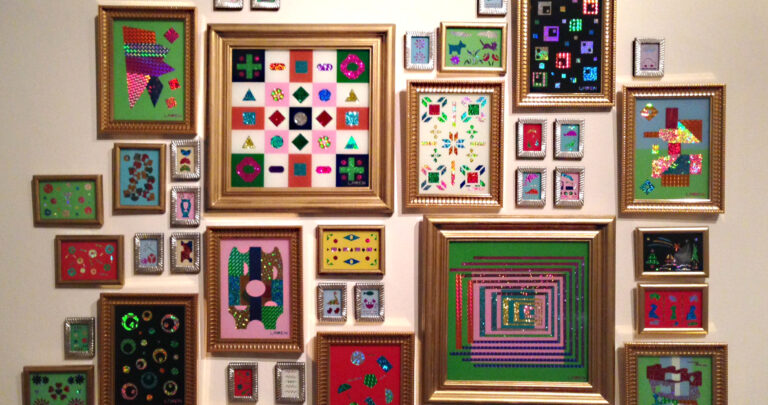

The reference to tombolas is present in several of his works. Greco was an enthusiastic and assiduous participant in the tombola games of the popular fairs both in Madrid and Piedralaves and, inspired by them, he projected an exhibition in 1963, which finally never took place. He cut out some of his drawings and placed the fragments in paper envelopes. On the front, he wrote different legends that, like in raffles and popular tombolas, announced a “surprise” content: “Always with the latest news, Greco will inform you. Check its interior ”,“ Each envelope comes with a signed memory ”,“ Your whole family will envy you for having this legitimate Greco”, “Surprise envelope. Check its interior”. Greco intended to turn his exhibition into a raffle, affecting the institutional art orders with the street dynamics and the popular fair.

The tombola is also alluded to in the numbers that Greco drew in his inks and collages from 1963 and 1964. Greco seems to have composed his drawings in episodes, as if they were the draft of a novel, but also as the disordered pages of a notebook. As in his notes, Greco’s drawings record a tremor of writing that scrawls with the body. His works are also constellations, erratic cartographies, secret maps to roam the city.

1 Antonio Saura, “Glosa con cuatro recuerdos”, Greco, Buenos Aires, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1992, p. 19.

2 Diego Trerotola, “El pintor de los baños”, Página/12, Suplemento Soy, 29 de julio de 2011.

3 His friend Adolfo Estrada, Ada Barrier and his husband Carlos Mazar, Doña Maura, owner of the house in Piedralaves where Greco stayed for a season, Manolito, waiter at café Gijón, Gonzalo Torrente Malvido (jr.) and his wife, Brigitte, between others.

4 I want to thank Paula Pellejero for sharing her research about this project, one we know little about.

view more

exhibition

press

other exhibitions

Axel Straschnoy, Beto De Volder, Clorindo Testa, Emilio Pettoruti, Enio Iommi, Esteban Pastorino, Gyula Kosice, Manuel Espinosa, Marcela Cabutti, Matilde Marin, Rogelio Polesello, Romina Ressia, Romulo Macció · 12.12.2023 - 15.02.2024

Indefinit

Axel Straschnoy · 02.11.2023 - 29.12.2023

Brave the Heavenly Breezes

André Komatsu, Enio Iommi, Clorindo Testa · 23.08.2023 - 31.10.2023

Hiato

Mariela Vita · 12.07.2023 - 16.08.2023

GEJIGEJI

Polesello, Aizenbeg, Kosice, Vardanega, Le Parc, Iommi, Puente, Arden Quin, Espinosa, Demarco, Straschnoy, De Volder, Pastorino, Imola, Batistelli, Cabutti, Reyna · 09.02.2023 - 15.03.2023

Eléctrico/ ecléctico

Fabiana Imola & Aníbal Brizuela · 16.09.2022 - 02.12.2022

Inside, the shapes. They move alone

Romina Ressia · 09.06.2022 - 25.08.2022

Grow flowers

Martín Reyna · 11.03.2022 - 03.06.2022

Color in transit

Matilde Marín · 08.02.2022 - 02.03.2022

25FPS

Clorindo Testa · 11.11.2021 - 31.01.2022

Testa, projects and other games

Cabutti, De Volder, Reyna, Imola, Ventoso, Ressia. · 05.10.2021 - 22.10.2021

Group Show 2021 II

Matilde Marín · 23.07.2015 - 21.09.2015

Undetermined landscapes

Marcela Cabutti · 16.07.2021 - 22.09.2021

Balcarce, topographic memories of a landscape

Benito Laren · 12.05.2012 - 22.06.2012

Casino

Lila Siegrist · 26.06.2012 - 27.08.2012

Vikinga Criolla

Cárdenas, Imola, Marin, Res, Sommerfelt, Ventoso · 10.08.2012 - 11.10.2012

Morphological confrontations

Martin Reyna · 20.09.2012 - 20.11.2012

Reyna in the horizon of color

Romina Orazi · 04.12.2012 - 04.02.2013

Subject to infinite division

Aizenberg, Boto, Espinosa, Iommi, Lozza, Le Parc, Kosice, Silva, Tomasello, Vardánega · 01.06.2013 - 31.07.2013

Dimensional

Antoniadis, Marín · 07.09.2013 - 07.11.2013

Double contrast

Andrés Sobrino · 28.03.2013 - 30.05.2013

Andrés Sobrino

Antoniadis, Cabutti, Laren, Reyna, Florido, Sobrino, Straschnoy, Tarazona, Ventoso · 20.12.2013 - 15.02.2014

Universus

Elena Dahn · 25.03.2014 - 26.05.2014

Elena Dahn

Marcela Cabutti · 15.07.2014 - 15.09.2014

Finding meaning through shapes

Axel Straschnoy · 12.11.2014 - 19.01.2015

La Figure de la Terre

Fusilier, León, Quesada Pons y Vega · 15.03.2015 - 30.04.2015

Limbo

Luciana Levington · 28.05.2015 - 24.07.2015

Luciana Levinton

Leo Battitelli · 12.11.2015 - 12.01.2016

Gargalhadas

Hasper, Scafati · 10.02.2016 - 11.04.2016

Womens’ double

Axel Straschnoy · 12.05.2016 - 13.06.2016

Today, great tomorrow!, in the pines wind blows from the past.

Arden Quin, Boto, Demarco, Espinosa, Iommi, Le Parc, Lozza, Polesello, Puente, Silva, Testa, Tomasello · 07.06.2016 - 05.08.2016

Masters of the avant-garde

De Volder, Sobrino · 11.08.2016 - 10.10.2016

Andres Sobrino and Beto De Volder

Battistelli, Cabutti, Cacchiarelli, Sobrino, De Volder · 02.01.2017 - 28.02.2017

2017 Group Show

Fabiana Imola · 28.02.2017 - 14.04.2017

The forest, the rain and other scenes

Alberto Heredia · 06.09.2017 - 11.10.2017

Alberto Heredia

Federico Manuel Peralta Ramos · 31.10.2017 - 29.12.2017

Federico Manuel Peralta Ramos

Marcela Cabutti · 10.11.2017 - 31.01.2018

About the effective distance between objects

Luciana Rondolini · 15.02.2018 - 15.04.2018

End

Estanislao Florido · 27.04.2018 - 01.07.2018

The disenchanted object

Battistelli, Cabutti, Marín, Straschnoy, Ventoso, De Volder · 06.07.2018 - 31.08.2018

2018 Group Show

Rogelio Polesello · 06.09.2018 - 20.12.2018

Vortex

Cabutti, Imola, Marín, Reyna, Rondolini, Straschnoy, De Volder · 27.02.2019 - 03.04.2019

2019 Group Show

Matilde Marín · 25.09.2019 - 31.12.2019

As the blue smoke of Ítaca is spotted

Esteban Pastorino · 10.09.2020 - 29.01.2021

Pastorino

Marín, Imola, De Volder, Reyna, Florido, Straschnoy, Pastorino · 08.02.2021 - 01.04.2021

2021 Group Show

Alberto Greco · 06.04.2021 - 30.06.2021

LA PITTURA È FINITA. Poses and impostures of Alberto Greco in Italy